“Travel gives you consciousness — and then that consciousness inspires you to travel even more”

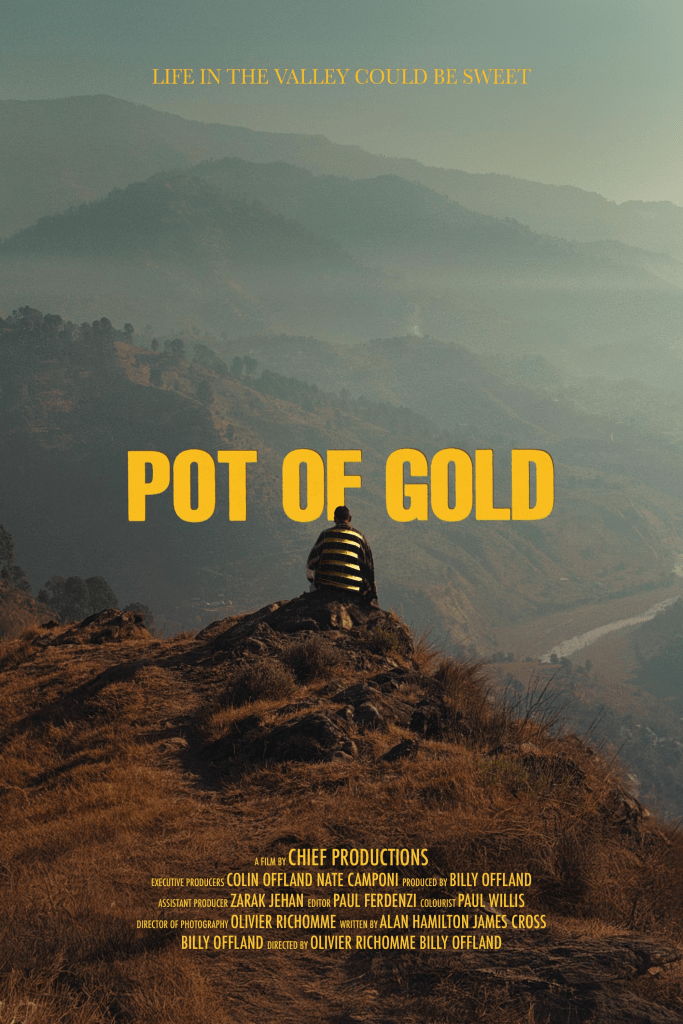

Please watch Billy Offlands Documentary Here on Prime Video : https://www.primevideo.com/detail/Pot-of-Gold/0NIFG9AJ2NTKVSZNA7T92IR401

Billy Offland, 27, is the youngest verified Brit to have visited all 193 UN-recognised countries, according to Nomad Mania. But the statistic collapses quickly under its own weight. Because once you’ve crossed every border travel stops being aspirational and starts becoming ethical. This piece isn’t about finishing the world. It’s about what remains when movement turns into responsibility, when seeing too much makes ignorance impossible, and when travel no longer lets you look away.

What struck me wasn’t the achievement, but the philosophy that shaped it.

Billy grew up travelling. Not the kind of travel defined by resorts or rigid itineraries, but trips driven by curiosity and discomfort. His father believed in “seeing places before they were ruined” — a phrase Billy acknowledges is loaded, but also honest. It meant places like Bosnia and Herzegovina, remote Argentina, Oman, Indonesia long before its quieter corners became mainstream, and a childhood where school holidays stretched into experiences rather than escapes. Travel wasn’t a break from education; it was education.

That early exposure planted a seed. Billy didn’t grow into a traveller chasing novelty — he grew into someone chasing understanding.

By the time he was travelling solo, that mentality had hardened into instinct. He worked in São Tomé and Príncipe, crossed Madagascar, earned his divemaster certification, and slowly stitched together a worldview shaped by repetition and contrast. Diving became a turning point. Seeing coral reefs up close — not once, but repeatedly — changed everything. Places like the Maldives, pristine one year and visibly deteriorated the next, made environmental decline impossible to ignore.

“People don’t act because they don’t see it,” he said. “When you see it physically, it hits differently.” Indonesia became central to this awakening. Raja Ampat in West Papua, Bunaken in Sulawesi — underwater worlds so alive they felt unreal. But even there, urgency lingered. Climate change and coral reefs are not patient companions.

This awareness shaped how Billy travelled next. He didn’t just move through countries — he embedded himself within stories. He sought environmentalists, conservationists, and people living at the edges of global systems. From Congo to the Central African Republic, from Cameroon to Djibouti and Somaliland, he saw both collapse and resilience. Dzanga-Sangha National Park in the Central African Republic stood out — a place so remote that just reaching it felt like a commitment. But that commitment mattered. “If people don’t go,” he said, “those places lose support. And then they disappear.”

Yet Billy is honest about the weight of it all. Global environmental collapse is overwhelming. UN conferences feel distant. Policy feels abstract. What saved him from paralysis was reframing scale. “If you get scared by the size of the problem,” he told me, “break it down to something local.” Pick a reef. A forest. A valley. A species. “Pick your passion and try to do whatever you can.”

Despite visiting every country, Billy doesn’t romanticize constant interaction. In fact, much of his travel was quiet. Walking markets with AirPods in. Observing. Blending in. “You’re interrupting someone’s normal life,” he said. “That’s a privilege.” He’s wary of loud tourism, of presence without respect. His approach balanced observation with participation — knowing when to speak and when to disappear.

That said, some interactions are unavoidable — especially when travelling solo, on a budget, over land. Billy crossed Africa largely by bus, moving continuously through countries rather than hopping between capitals. That style forced connection. You speak to drivers. To strangers beside you. You ask questions because you have no plan. “Local knowledge is everything,” he said. “If people come to Manchester, good luck finding the good places without asking someone.”

We spoke about the difference between “travel” and “holiday.” Billy doesn’t judge either, but he’s clear: deep travel is hard. It takes time, skill, patience, and a tolerance for discomfort. Crossing from Djibouti into Somaliland, pushing deep into Congo’s rainforest, or navigating Central African Republic is not aspirational content. It’s exhausting. “Most people wouldn’t enjoy it,” he said. “And I don’t blame them.”

But for a few, there’s an obligation — especially when that travel supports fragile ecosystems or forgotten communities. And even that phase doesn’t last forever. “I couldn’t replicate that travel now,” he admitted. Youth, resilience, and foolish courage played their part. Some journeys are time-bound.

I never ask my guests their favourite country, instead I ask them what are some regions or places which hold a special place in their heart. For Billy, Indonesia topped the list for depth and accessibility. Damascus in Syria stood out historically — one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities, layered with memory. Africa offered unmatched adventure. Brazil surprised him with simplicity — beaches, presence, ease. Uzbekistan gave him a surreal memory: a techno festival on the banks of the Aral Sea. Context defines experience.

Diving surfaced again when we spoke about community. Whether in Malaysia’s Tioman Island, Southeast Asia, or beyond, dive shops form instant tribes. Sport does the same. Billy spoke about wearing a Manchester United badge across Africa, playing rugby in Fiji, football with Afghans in Pakistan, cricket opening doors across India and Pakistan.

One of the most grounded moments of our conversation centred on Azad Kashmir in Pakistan. Billy spent months there filming a documentary on beekeepers and honey production called “Pot of Gold” — not in the tourist-heavy northern regions, but in a quiet valley called Dir Kot. There was no reason to go there unless you had purpose. Heavy militarisation contrasted with extraordinary warmth. Tea. Community. People dropping in unannounced. “People are not their politics,” he said. “Most people are just thinking about lunch and their kids.” I have seen this documentary and it is absolutely stunning. The cinematography and the underlying message of climate change is absolutely beautifully told.

Yet he also acknowledged a blind spot. Solo, deep travel can miss broader political and historical context. Guides, often dismissed by independent travellers, offer something essential. Billy admitted he looks forward to returning to places like Pakistan, Syria, Brazil, or Tunisia with less time and more structure — forced to listen, to contextualize, to zoom out.

If dropped into a new country tomorrow, Billy wouldn’t open a map. He’d walk. Find food. Sit down. Ask questions. Photography, for him, is just another excuse to move slowly, to wait, to notice.

This conversation wasn’t about finishing the world. It was about relating to it. From Japan to Malaysia, Singapore to Indonesia, Congo to CAR, Pakistan to Indian Kashmir by reflection, Tunisia to the United States, Palau, Micronesia, Marshall Islands, Kiribati, Nauru, Fiji, Thailand — the geography mattered, but the insight mattered more.

Travel, when done honestly, doesn’t simplify the world. It complicates it. And maybe that’s the point.