“Follow Your Heart, Just Go“

Follow Boris Here on his website : https://boriskester.com/

Read the Preface of his book here : https://boriskester.com/preface/

See his stunning images here : https://www.traveladventures.org/

Follow him on instagram here : https://www.instagram.com/boris_traveladventures/

The first thing you notice when speaking to someone who has travelled to every country in the world is not the number itself. It’s calm. The clarity. The sense that they have seen enough of humanity — its beauty, its contradictions, its patterns — to understand something the rest of us spend years trying to grasp.

My conversation with Boris Kester carried exactly that feeling. There was no grand introduction, no dramatic claim about having completed all 193 nations. Instead, there was a quiet confidence shaped by decades of movement, thousands of encounters, and a lot of curiosity.

Boris told me he wasn’t born with the dream of visiting every country; no one is. But his life began in motion. At just five months old, his parents placed him in a travel cart and took him on a two-day train ride to Greece, followed by a boat to Crete. Even before he could “walk or talk,” he was absorbing foreign sounds, foods, people, and rhythms. He didn’t consciously remember any of it, “but this is what basically started to make me a traveler,” he said. Before turning ten, he was keeping diaries and excitedly counting countries.

Much later, after passing the halfway mark without ever intending to, a major life event pushed him to reevaluate everything. “That’s when I decided: this will be my life goal.” He committed to the remaining 75 countries with purpose, discipline, and curiosity.

As he spoke, I felt echoes from my own childhood — being pushed through Hong Kong in a pram, scratching countries off my gifted map, widening my world one tiny patch at a time. Some people stumble into travel while are quietly shaped by it long before they realise. As we called it, we caught the travel bug. What we both shared was curiosity. “We share a very genuine curiosity,” he said. “You look at a map and imagine every place — and you want to know what it actually looks like when you go there.”

But as we discussed, many people today avoid the unknown. They chase the familiar: Paris, Italy, Santorini, the places everyone posts. Others avoid entire regions because of misconceptions, stereotypes, or fear. I told him how people ask me where Tunisia is when I mention I’m going — as if the unfamiliar is automatically unsafe or unworthy.

Boris nodded, and his perspective was sharp: “People should travel where they want — but they miss out on so much. Famous places are crowded every day of the year now. And unknown places hold the real magic.” He emphasised that most negative assumptions are just that — assumptions. “The reality on the ground is almost always very different from the image you have before going.”

That led us to the essence of travel: people. For him, travel is far less about scenery than human connection. “In the end, travel is about connecting — understanding how people live and why they do things the way they do.” And this connection goes both ways. Locals ask where he’s from, what his life is like. Stories are exchanged, worlds grow larger, and stereotypes dissolve.

His encounters illustrated this beautifully. When he was 18, two Moroccan boys befriended him, eager to practise English — until they suddenly tried to recruit him into a drug-smuggling deal. A harsh early lesson: some people have agendas. But the very next year, in Finland, when he lost his wallet, a poor elderly couple took him into their home, fed him, sheltered him, and even paid for his return journey.

But the story that reshaped him most came from a remote island in Kiribati. When asked where he was from, he explained the Netherlands — near Germany and France. The man looked confused and asked, “So how many hours by boat between Netherlands and Germany?” When Boris explained there was no boat — you could drive, take a train, even walk — the man was stunned. “Why would you have borders if there is no sea?” he asked. And suddenly it clicked for Boris: for people whose entire lives revolve around islands, land borders make no sense. “It made me question why borders exist at all. Countries are invented by humans — arbitrary lines. Yet we treat them like absolute truths.”

He also told me about a moment in Sudan that stayed with him forever: a mother and her young son, clearly poor and wearing worn-out clothes, whom he had spent a long bus journey wondering how he might help, only to discover at the end that they had quietly paid for his ticket without even telling him — an act of generosity that left him humbled and emotional.

That revelation fed into a lesson travel taught him. “When you speak to people one-on-one, you realise we are so similar. But at the same time, people fear others who look or sound different. That is the tragedy of humankind.” He added, “99.9% percent of people are good. They’ll help you, welcome you, feed you. But we still generalise and say ‘those people are bad.’ It makes no sense.”

Eventually, we reached his final country. Strangely, it was not a remote Pacific island or a war zone, but Ireland. Most travellers save the hardest nation for last — Yemen, Somalia, Nauru. But Boris planned differently. “I wanted to celebrate with family and friends. If I finished in the Pacific, no one would come.” So he held Ireland for the end. He walked over the border from Northern Ireland, knowing that the moment he took one more step, the quest of almost 20 years would be complete. It felt surreal. The real emotion came later, standing before the UN Headquarters in New York, walking past each flag from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe in alphabetical order, remembering — really remembering — every story, every struggle, every kindness.

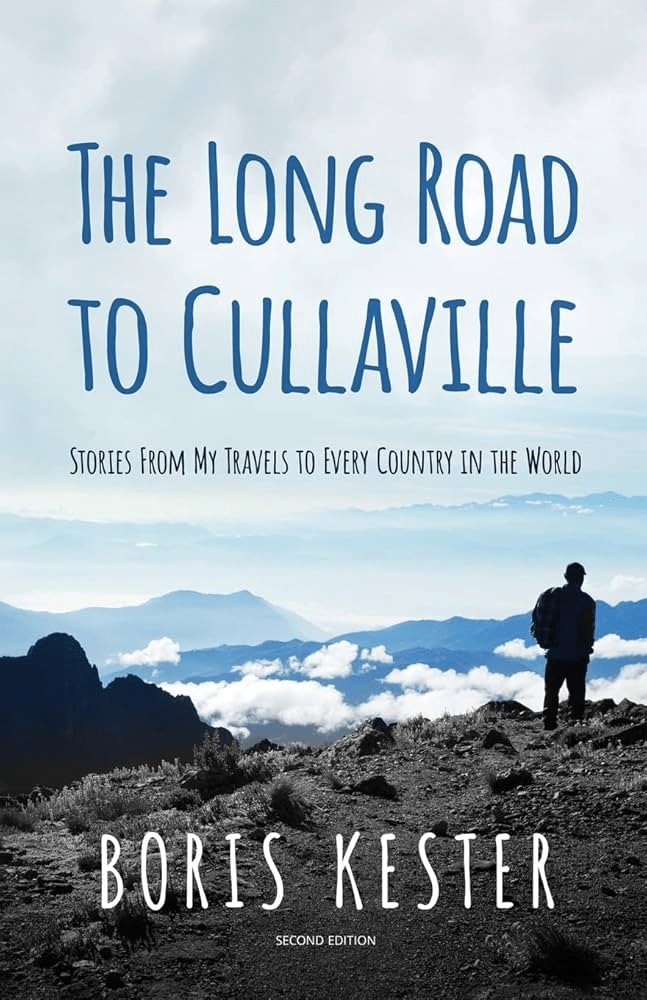

Those memories became his book, The long road to Cullaville. It isn’t a guidebook. It isn’t about attractions. It is about reality — the unseen, unheard, unfiltered truth of places we misunderstand. He wrote it because people constantly asked if travel was dangerous. “I wanted to show the reality, not confirm the bias,” he said. He is soon publishing his second book Wonderheart, whose message is clear: “Follow your heart, don’t be afraid.”

I asked what still excites him now that he has been everywhere. His answer was simple and beautiful. “Curiosity. This naive, pure curiosity. Even a small waterfall can make me emotional. Just knowing I’m going to see something new already excites me.” I understood instantly. I had once stood before a simple wadi in Oman and felt unexpectedly emotional — not because it was the largest or most famous, but because something inside me shifted. Some places touch a part of you you didn’t know was waiting.

When I asked him to name places that truly fascinated him, he immediately mentioned the Pacific, admitting he had once assumed it would be dull because he imagined nothing more than beaches and small islands, but after spending three months travelling through the region, he realised how wrong he had been: “The Pacific surprised me more than anything,” he said, describing volcanoes, ancient ruins, wildly different cultures and how “every island has its own identity.” He added that when you travel with an open mind, almost every country surprises you — not always in big ways, but in the small, intimate moments that stay with you long after you leave. So I asked him a question I pose to every traveller: if he were dropped into a completely new place, how would he explore it? He didn’t hesitate: “I’d try to meet someone,” he said, explaining that his first instinct is always to talk to a local, find a common language if possible, and understand the place through the people who live there, because that, to him, is where the real soul of a destination lies.

When I asked what advice he would give to a 19-year-old traveler like me, he smiled. “Just go. Don’t rush. Take your time. Don’t be afraid. Travel slowly, and you’ll learn more than any school or college can teach you.” We also spoke about privilege — and how we admire travelers from Malawi, Togo, or countries with weaker passports, especially women who navigate far greater challenges yet still chase their dreams. “It proves anyone can travel if they truly want to. It may be harder, but not impossible.”

The world is vast, complicated, gentle, chaotic, heartbreaking, beautiful — and overwhelmingly human. And if there is one lesson we can carry from someone who has seen every corner of it, it is this: Follow your heart, not the map. The world will meet you halfway.